Women and discriminatory application of the death penalty

The World Congress had never before devoted a session to the specific experience of women. The discussion raised and began to explore a number of important questions.

Lack of data

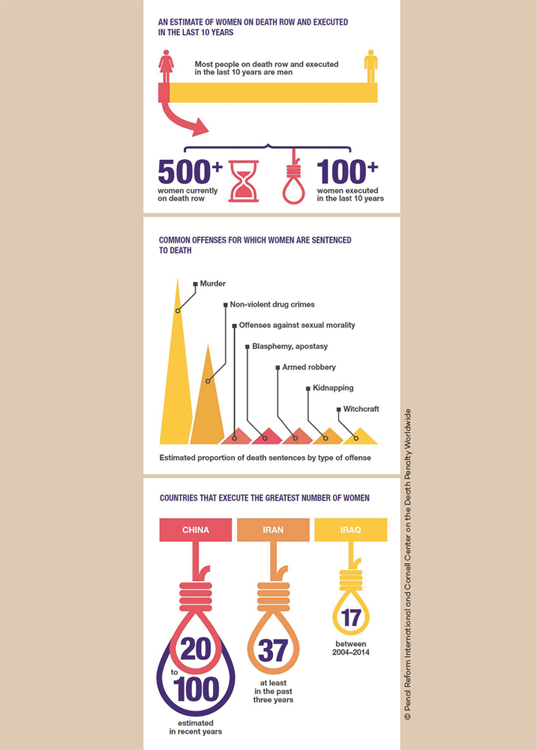

Introducing Judged for More than Her Crime, a report that reviewed the global situation and experiences of women condemned to death, Delphine Lourtau underlined a basic problem: that there is little literature or quantitative information on women prisoners, especially women who have been sentenced to death. Women on death row have never been seen as a distinct category; they have always been adjunct to the male majority. As a result, those researching the Cornell report were not even in a position to assess accurately how many women have been sentenced or executed. It is true that women represent a small percentage of the death row population; but juveniles represent an even smaller minority, and their situation has been documented. Women on death row are currently invisible.

Given this situation, Ms Lourtau advised researchers to collect stories and testimonies to support their advocacy work. In the longer term, however, it is essential to obtain more information about the situation of women prisoners. She urged the abolitionist community to promote quantitative as well as qualitative research on this group of women. “While there are knowledge gaps, there will be advocacy gaps.”

Gender violence and female violence

All members of the panel noted that a very high proportion of women condemned to death are victims of gender-based violence, including child or forced marriage; and that many are condemned for murdering the partner responsible for that violence. Women rarely commit other forms of serious violence. Illustrating this point, it was noted that 102 Thai women have been sentenced to death in Thailand, all but seven of whom were sentenced for drug-related offences. This reinforces the argument that the situation of women prisoners, including women on death row, should be analysed in its own terms, separately from men.

Flawed judicial evaluation

Many jurisdictions do not (or did not in the past) accept pleas of self-defence in cases where women have killed partners who abused them. This failure of assessment is worsened by the fact that many courts do not or did not recognize that abuse accumulated over a long period can trigger extreme violence in a victim. In many instances, where the act of abuse that triggered the murder was not worse than the pattern of abuse that preceded it, courts have refused to consider pleas of self-defence or mitigation. In addition, although women tend to receive more lenient sentences because they are presumed to be less violent (a form of gender bias), women who are seen to have transgressed ‘female values’ (who are portrayed as Jezebels, adulterers, bad mothers, or femmes fatales) are judged harshly and are more likely to be condemned to death.

The nature of female criminality

The panel was asked whether “men are criminal by nature, whereas women become criminal because of their circumstances?”, sparking a discussion. Ms Lourtau said she resisted a gender essentialist approach, or the idea that women are not potentially violent. She thought it was dangerous to concentrate exclusively on women who are wrongfully imprisoned or who are survivors of gender-based violence. Focusing overly on female victims may obscure the fundamental case against capital punishment and the right to justice of both men and women who are guilty of crimes.

It is vital to recognize the specific character of women’s experience in order to apply a universal standard of justice.

The notion of women as victims

Ms Callamard took this argument further. From a human rights law angle, human rights advocates are bound to describe prisoners as victims because, in order to show that their rights have been violated, it is necessary to identify a ‘perpetrator’ and a ‘victim’. In this sense, human rights advocates will always press the case that women on death row are victims of State practices. “The fact that a woman is a cold-blooded killer does not mean she has not been victimized by the State.” Ms Lourtau agreed: in human rights law terms, women on death row are victims of the State; in the same way, men are also.

Taking the discussion of victimhood a step further, Ms Callamard went on to add that during the session some people had referred to ‘mothers’ rather than ‘women’, and the higher claims of mothers to protection. She thought that, while pragmatically the protection of children requires us to consider mothers, a focus on motherhood will not bring us very far. “There is no problem in considering that children are a mitigating factor, (…) but the image of themother can be dangerous if it is understood that the only women entitled to protection are women who have children.”

The specific experience of women

All these exchanges underlined that it is vital to recognize the specific character of women’s experience in order to apply a universal standard of justice. If societies do not recognize the differences of effect experienced by people with specific characteristics (men, women, children, minorities, etc.), systemic patterns of discrimination become invisible and members of those societies become complicit in the discrimination and denial that women and other minorities experience. This is a fundamental reason why it is essential to study the situation of women discretely, and to do so without explicit or implicit forms of special pleading or gender bias.

The importance of alliances

This raised a final issue. Ms Uwandu encouraged the abolitionist movement to “bring in new partners to the struggle” by making alliance with the women’s rights movement. She said that women’s organizations in Nigeria work for women in prison, but not for women on death row, because so few women are condemned to death. Even if they are few, however, women on death row have specific needs that must be addressed, and women’s organizations should be educated in abolitionist issues and encouraged to join the movement.

Challenges and recommendations

• It is essential to gather more quantitative information about the number and situation of women on death row.

• We also need more descriptions of the life stories of such women, including their treatment and experiences before and during their trial, and after sentencing.

Reading

The Cornell Center on the Death Penalty Worldwide, Judged for More than Her Crime: A global overview of women facing the death penalty (2018).

At: http://www.deathpenaltyworldwide.org/pdf/judged-for-more-than-her-crime.pdf

“What troubles me is the idea that women as a group must be seen as victims in order to receive clemency. I propose a framework where we can speak about individuals receiving justice.”

Delphine Lourtau

Executive Director, Death Penalty Worldwide, Cornell University