Abolition strategies: challenges and opportunities in Sub-Saharan Africa

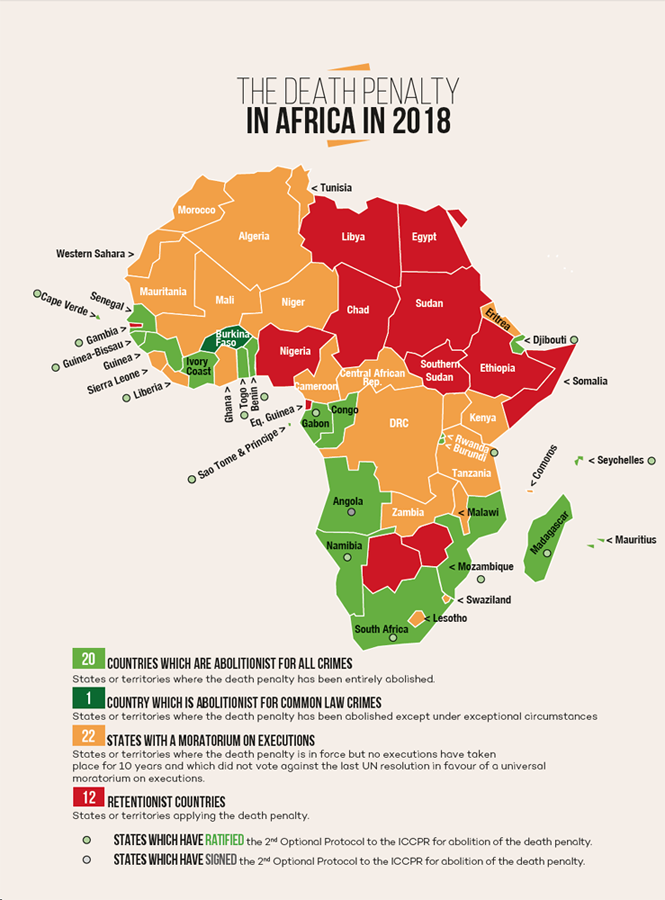

Sub-Saharan Africa is among the continents that have made most progress towards abolition. A number of countries nevertheless retain the death penalty. Nigeria, Sudan, South Sudan and Somalia continue to issue many death sentences. Somalia executed 20 people in 2016.

The discussion raised a number of key issues.

Regional action

At regional level, support for abolition of the death penalty has grown, but at the same time certain countries remain strongly opposed. An initiative at the level of the African Union that would have taken Sub-Saharan Africa towards a region-wide moratorium was blocked on procedural grounds in 2016. Diplomatic efforts continue to be made to establish a wider consensus on how to progress the issue.

Progress at national level

Several governments have taken steps towards ending the death penalty or its application, but the majority have preferred to introduce a moratorium or have removed the death penalty from the statute book rather than abolished it outright. (See case studies below.) In most instances, as government representatives explained, they have done so because politically this was the option that could succeed in Parliament, where opposition to abolition remains significant. Governments in the region have also become cautious after seeing efforts to reform blocked in some States, such as Morocco. In practice, reformers have taken a step-by-step approach: (1) adopt a moratorium, (2) reduce the number of crimes subject to capital punishment, (3) remove capital punishment altogether from the statute book, and (4) abolish the death penalty (preferably through the constitution).

Specific challenges face countries that practise sharia law, such as Sudan and Somalia, because judges in those countries may consider to be hudud crimes acts that are not crimes (or are misdemeanours) in other forms of jurisdiction. Some of these are capital offences. In Sudan, for example, apostasy, adultery and sodomy are punishable by death. Both socially and politically, the proximity of religious beliefs and law complicates efforts to reform.

Speakers argued that success depends on recognizing the specific context of each country and allowing each country to make progress towards abolition in its own way. They emphasized the importance of cooperating with civil society and other actors, addressing the core issues and discussing them with all parties.

Military law

In a number of legal regimes, capital offences are listed in the military as well as the civil code. It can take longer to remove these than to remove capital offences from the civil code. Militaries may be jealous of their prerogatives and reluctant to allow civil authorities to reform the military code; and where the civil authority is relatively weak, it may lack power to force reform. New governments with a popular mandate have been able to act; democratically elected governments that show firmness have also been able to impose their will. (See Guinea below.) At least in certain countries, nevertheless, the civilian authorities may be obliged to exercise discretion and judgement in this area.

Alongside negotiation and advocacy, training and raising public awareness are important dimensions of action.

Build consensus: dialogue locally, network internationally, build a coalition

Several speakers underlined that success depends on building alliances and addressing the concerns of key constituencies, including parliamentarians, officials in relevant ministries and commissions, the military and police, the media, women, youth, civil society organizations, religious leaders, and specific groups that support capital punishment – as well as regional and international agencies and networks that facilitate or promote abolition. Alongside negotiation and advocacy, training and raising public awareness are important dimensions of action. The case studies below illustrate some of the strategies that have been effective.

Speakers emphasized that political leadership can also be critical to successful reform, as it was in both Burkina Faso and Guinea.

“What matters is communication. To change minds, you need to bring on board religious leaders, organizations, civil society and other stakeholders that can have influence.”

Urbain Yameogo

Chair of the Coalition Against the Death Penalty, Burkina Faso

The African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights

The African Commission adopted a resolution in favour of continental abolition in 2005. Since then, it has worked with civil society, Governments and international institutions to collect information on death penalty and advocate for its abolition. The Commission’s Working Group on the death penalty in Africa is mandated to assess progress towards abolition and propose strategies and recommendations. In view of the fact that the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights affirms the right to life but makes no reference to the death penalty, The Commission adopted a draft protocol to the Charter which recommends abolition in States that already have a moratorium on executions and a moratorium on executions in States that still impose the death penalty. The draft protocol was submitted to the African Union (AU) in 2015 but subsequently blocked, because the AU did not present it in accordance with procedure. It is planning new strategies for moving forward, recognizing that certain AU member states are not yet willing to support abolition. The draft protocol would bridge the normative gap that currently exists in the Charter and provide restorative rather than retributive justice. (See the interview below with Maya Sahli Fadel.)

Guinea

The new Government in Guinea has declared a moratorium on executions, but achieving this outcome was not straightforward. The Government needed to take action at several levels and make progress slowly, step by step. In the Minister’s judgement, legislation to abolish capital punishment would have failed in Parliament, as it did in Morocco. The Ministry therefore chose to remove the death penalty from the new criminal code and replace it by a life sentence (30 years). Parliament voted unanimously in support of this proposal.

In addition, it was necessary to act urgently because a large number of prisoners were awaiting sentence, and important trials were pending following massacres in the Forest region. Swift action was needed to remove from courts the option of imposing capital sentences.

The Military Code in Guinea also authorized death sentences and the military lobbied to retain this punishment. The Government stood firm, however, arguing that it would be contradictory to retain the death penalty in one code and not in another.

Burkina Faso

Burkina Faso also declared a moratorium. The penal code authorized the death penalty from 1966; the military code and another law authorized it from 1972. Previous efforts to pass a draft abolition law were scotched by a coup attempt in 2015. After 2015, however, when the incoming Government undertook to prepare a new criminal code, it became possible to explore removing all references to capital punishment from the penal code.

Civil society was actively involved in the reform process, and a national coalition against the death penalty was formed. Inter-ministerial cooperation was supported by a civil society awareness campaign to bring the public on board. Meetings were organized with public institutions, government representatives and civil society. The Minister, an abolitionist, was also supportive. This wide alliance, including the executive, was decisive. Burkina Faso adopted a new Penal Code in May 2018 that removed the death penalty.

The death penalty remains in the Military Code (and in the railways police law).

Kenya

Though no executions have been carried out in Kenya since 1987, the country retains a mandatory death penalty, for which public support remains high. In 2018, the Attorney-General appointed a Taskforce to review the mandatory nature of the death penalty, which recommended its abolition.

Its finding is currently only a recommendation, which must be turned into law by Parliament. Ms Njau-Kimani, Chair of the Taskforce, recognized that this step will require the goodwill of both the judiciary and the political elite. Though she was optimistic, she observed that “the death penalty is regarded as the most effective punishment for violent crimes and there is also some lack of faith in the justice institutions”. Kenya remains in a relatively early phase of the abolition process.

Sudan

In January 2019, the prospects for abolition in Sudan were not promising. Sudan had among the highest rates of capital punishment in Africa. More than 49 individuals were currently held on death row. Under Sharia law, the death penalty was applicable to a number of crimes defined by the Koran as hudud crimes, including apostasy, adultery, and sodomy as well as murder. Modes of execution included crucifixion, hanging and stoning. Unfair trials are an issue. Many detainees lack legal representation; many have been tortured.

Capital punishment also had a political dimension. Political activists and human rights defenders have been executed. A number of Southern Sudanese were sentenced to death for having joined a rebel group, but subsequently released after the Government signed an amnesty agreement with the group in question. It is critical, first of all, to reduce the number of crimes that carry the death penalty, and bring Sudanese law in line with the African Charter. Sudan has accepted the authority of African mechanisms, but rejected international standards. It will be important to bring cases before UN human rights bodies, but to date this work has been done from abroad because human rights defenders were often denied permission to leave Sudan.

Democratic Republic of the Congo

The DRC’s criminal and military codes both authorize the death penalty for certain crimes but the last execution occurred in 2003. There is therefore a de facto moratorium. Efforts have been made to raise the issue in Parliament, and a parliamentarian submitted a draft abolition law in 2010. However, no law has been passed, partly because of the DRC’s dysfunctional institutional culture. The military has opposed abolition.

The DRC ratified the Rome Statute in 2002. However, the DRC’s implementing law (2015) authorizes the death penalty for crimes that may be capital crimes under the Rome Charter.