The death penalty and LGBTI persons

It was noted to start with, that the death penalty (where it is not abolished) is restricted under international law to the most serious crimes, which do not include expressions of sexual orientation and gender identity (SOGI). Dr Agnes Callamard underlined the important role that expressions of SOGI play as identity markers. Taken in conjunction with sex, gender and class, they predict a person’s exposure to risk or lethal harm.

It was also noted that reliable information is not available on either the sentencing or detention conditions of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and intersex (LGBTI) prisoners, and more work needs to be done to document their numbers and treatment.

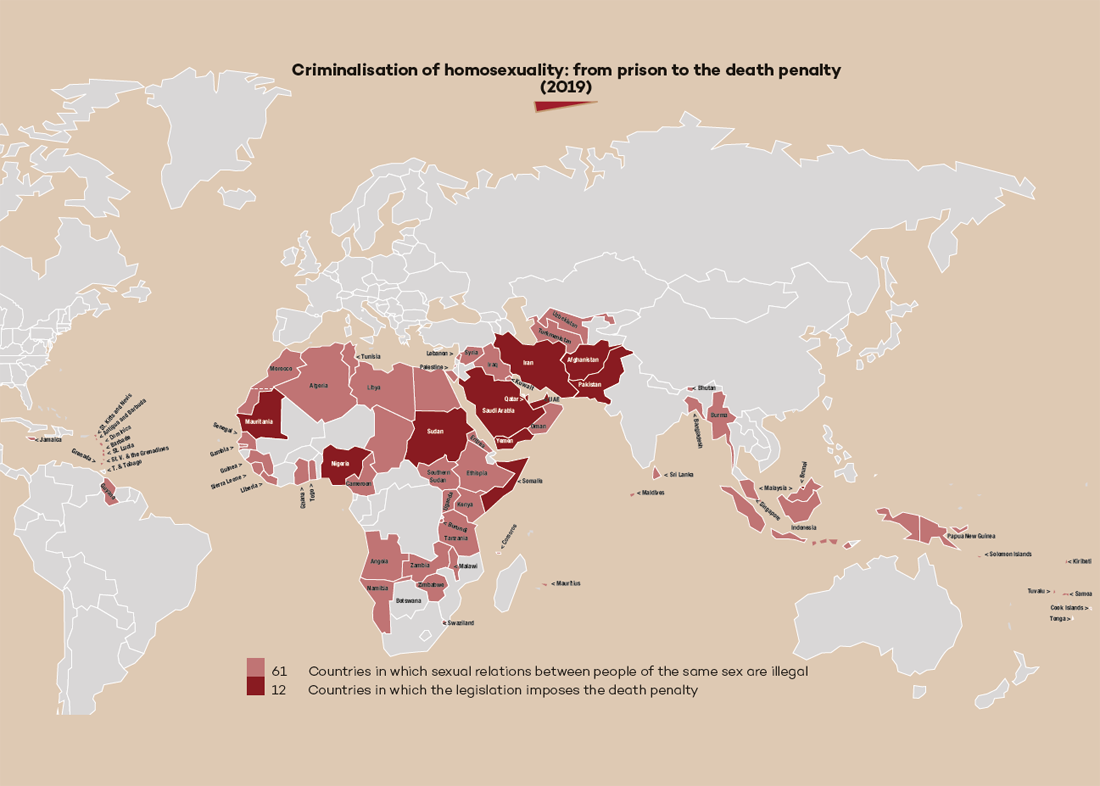

The discussion raised a variety of threats that LGBTI individuals face because of their sexual orientation and gender identity. They include: the threat of execution in countries that still impose the death penalty for homosexuality or other expressions of SOGI; the dangers of imprisonment for the same ‘crimes’ in certain countries; the execution, mistreatment and abuse faced by LGBTI individuals at the hands of some non-State armed groups; and the general risk of killing and persecution that LGBTI persons face, exacerbated by the State’s failure to either protect them or investigate crimes against them.

Persons perceived to be LGBTI suffer the same discrimination as those who are LGBTI.

The right to life means much more than the right not to be killed. It contains intrinsically the notions of dignity, security and integrity. From this perspective, many people in the LGBTI community are deprived of enjoyment of the right to life. Quoting a trans woman who described her life as a “slow death”, Agnès Callamard noted that the life expectancy of trans women is significantly lower than average.

Poverty is an exacerbating factor. The majority of people condemned to death belong to the poorest ranks of society, deepening its inherent bias.

“If you cannot imagine putting someone to death for engaging in consensual, adult, same-sex activity, how can you accept the death penalty for people because they are poor?”

Agnès Callamard

UN Special Rapporteur on extrajudicial, summary or arbitrary killings.

Risk of execution

In this context, the greater risk to LGBTI people is not the death penalty but criminalization more generally. No executions on the basis of SOGI have been confirmed in the last 12 months. What needs to be emphasized is that legal systems that discriminate against LGBTI people increase their vulnerability and increase the risk that they may suffer extra-judicial discrimination, violence or death.

Execution by non-State armed groups

By contrast de facto governments and certain armed groups do execute LGBTI people, extra-judicially or following deeply flawed quasi-judicial processes. Daesh (or ISIS), for example, killed both men and women for their sexual orientation, but other groups have been guilty of similar crimes. Such crimes should be prosecuted, under international human rights law or national criminal law, but it remains difficult to hold non-State actors accountable because they are not always bound by international law and mechanisms of recourse are almost non-existent.

Denial of due process

A further concern is that, in States that impose the death penalty for SOGI, or criminalize certain expressions of SOGI, trials are not fair and LGBTI persons rarely have access to a proper defence. Many LGBTI detainees do not have access to legal aid and therefore cannot defend themselves adequately. In too many jurisdictions that criminalize LGBTI identity, LGBTI persons are deprived of their human rights.

Risks in detention

Specific issues arise when LGBTI persons are detained. Whether LGBTI people are on death row because of their SOGI status and for other reasons, LGBTI detainees are particularly at risk from violence, and may be killed as a result of official negligence, or intentionally, because of who they are. In Chechnya, for example, some LGBTI were tortured to death because they were LGBTI.

Trans and intersex people also face particular risks if they do not receive medicines they need; some States, such as Vietnam, do not make such medicines available.

Wider risks of persecution and lack of State protection

All the speakers underlined that LGBTI people face the greatest risks outside the judicial process. Many States fail to protect LGBTI people or are complicit in violence against them. In some regions, States tolerate honour killings of both men and women and perpetuate practices that make prosecution of those who commit them improbable. Mr Zaidi listed a number of brutal cases of violence1. A Syrian trans woman was killed in Turkey in 2016; the police did not investigate her death. When a Nigerian lesbian reported her father to the police after he beat her, she was shamed and told that she could not report violence committed by her father. An Algerian man had been murdered 18 days before the panel. The killers used his blood to write in English “he is gay”, thereby ostracizing him and his family, shaming him in death, linking homosexuality to Western ideas, and socially validating his murder.

Political and cultural concerns

The speakers agreed that many people consider LGBTI identities to be ‘foreign imports’ borrowed from the West. As a result, the international community and Western governments can put LGBTI people at risk when they demand decriminalization. It is usually more effective to promote social acceptance of LGBTI. For similar reasons, when religious leaders or scholars condemn LGBTI identities, it is usually better to engage them in discussion rather than attempt to impose alternative opinions on them.

Nikki Brörmann described how COC, her organization, works with community based organizations to share information on the ground. In her experience strengthening and supporting local movements and helping them to do the work themselves is the best way forward, because local movements know their context and risks, and what they need.

Governments can still play an important role by providing safe spaces and emergency response capacity, to help those on the ground.

Challenges and recommendations

• It is important to strengthen mechanisms to increase the accountability of non-State actors who execute or commit other crimes against LGBTI people.

• It is also important to remove the impunity of individuals who commit honour crimes; States should be pressed to prosecute all such crimes.

• Efforts should be made to improve prison conditions for LGBTI detainees, and protect them from harassment and violence of all kinds.

• Efforts should be made to document and prevent anti-gay propaganda emanating from Western groups, including conservative churches originating in the US.

To read